The lights dimmed and I wondered if the goosebumps were from the theatre’s chill air or the sensation of finally witnessing a shade of Japanese culture with my family in the same space. After years of attempting the seemingly impossible, the stars and busy schedules aligned at last with my mother, father, and younger sister joining me for a 3-day jaunt in Tokyo. We walked the Center Gai crosswalk in Shibuya, did the lanes of curious seafood in Tsukiji, and now here we sat in Ginza’s Kabuki-za as the central stage lit up, revealing an old temple. Hanging inside it was a gigantic bell and as I plugged in the earphones and leaned back, the narrator began the tale of a ghost come to destroy it…

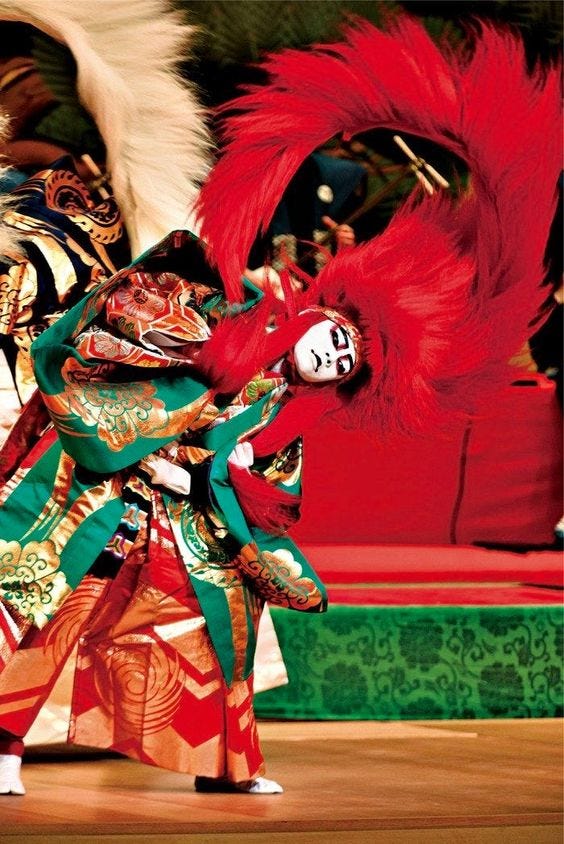

Of all the forms of traditional Japanese theatre1, Kabuki is the most kinetic, the most vibrant. It is known for its stylization of historical accounts and epic tales through song, dance, and radiant pyrotechnics. Even if you’ve never heard of Kabuki itself, chances are you’re familiar with the iconic look of some of the actors whose faces are elaborately painted in white and wild strokes of red. Kabuki (歌舞伎) is composed of three characters meaning “sing”, “dance”, and “skill”, and it originated as many performing arts did, in the red light district.

Originally an all-female entertainment troupe, kabuki was pioneered by Izumo no Okuni in the 17th century. It gained immediate fame as the female artists parodied everyday life in the roles of men and women. However, towards the end of the century, the performances were deemed “too erotic” and female kabuki was eventually banned in favor of the modern-day all-male variety, or yaro-kabuki (young man kabuki). This began the Genroku era, a golden age when kabuki thrived and became a more official, streamlined art. Audiences could expect to see established conventional character types and professional kabuki playwrights, like the great Kawatake Mokuami (1816), begin to rise in prominence. Actor Ichikawa Danjuro is said to be the inventor of kabuki’s bizarre, static poses called mie and even the kumadori and kesho make-up that resembles a mask, or a strange doll.

When discussing the elements of the kabuki play, keep in mind that it was originally created to entertain the common people: unpretentious and immersive. This is evident even today in the design of the stage with its hanamichi, or flower path, stretching out from the main performance area and into the audience. Trap doors and revolving sets allow for dramatic entrances and exits of the actors while backgrounds can be changed even mid-performance by stagehands dressed entirely in black. A performer is not necessarily grounded by gravity either, as wires can hoist them over the stage or other parts of the auditorium in a technique familiar to many of us called chunori, “riding in mid-air”. Actors are under intense pressure during performances to portray multiple roles and are awaited backstage by a team ready to help them don new costumes and makeup at a moment’s notice. They can be complemented during the show by yelling out their yago, a name they’ve received in the kabuki troupe, or even more by calling out their father’s name.

It was these calls to the star of the show that I heard while sitting in the upper rows of the Ginza theater as the crowd began to applaud his performance. A sheepish smile crept across my face — I really wasn’t used to such a welcome interactivity between the crowd and artists on stage. As shows can easily become an all-day affair depending on the play, my family and I stayed for one act before heading out to discuss the experience. As for the story of the ghost? The play is called “Musume Dojoji”2, which turned out to be a classic selection.

The theatre in Ginza has been renovated in recent years. Why not stop by for what could be a transporting experience? The feverish blend of wild colors, special effects, and actor’s brazen faces successfully lured me to another place — not really the past as it had been, but rather the Kabuki’s mad interpretation of it. Believe me, I wanted to stay awhile. Maybe you will too.

The traditional theatre arts of Japan, with some dating back to the 15th century. Noh is a spiritual play where the performer walks and speaks in slow movements while wearing mysterious masks. Kyogen, a more humorous art, was originally meant to entertain between Noh acts. Kabuki is more theatrical, as stated above. Bunraku concerns puppetry, and Yose a spoken drama.

Formally known as Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji (京鹿子娘道成寺) or “The Maiden At Dojoji Temple”, this play is the oldest surviving Noh-based Kabuki theatre drama. It concerns a girl dancing in front of a bell in Dojoji Temple before revealing herself as a serpent demon. Geishas have been known to learn parts of the many dances to perform in their own private shows.